The ocean is full of wonderful and amazing animals, some of which defy our imagination. These colorful and sometimes weird looking critters demand our attention to detail, especially when it comes to photographing them. If the lighting isn’t spot on, or the composition is poor, a potentially fantastic shot will fail to excite our audience. Take the flamboyant cuttlefish for example. They flash their colors when they are hunting or excited. They have a unique hunting behavior, and when they mate, there are usually several males harassing a larger female.

These behaviors are something we strive to capture so that we have a compelling image, but how can we maximize our efforts? If you have a look at the cuttlefish in the bottom right hand corner of the gallery above, you will see that it is not a very interesting image. The cuttlefish is behaving well, displaying its colors and posing nicely. But the lighting on this image is spread too widely and the cuttlefish doesn’t stand out from the sandy background. The image at the top left is of another cuttlefish exhibiting the same behavior, but it is lit using a snoot from above. This has a spotlight effect which isolates the animal from it’s environment, producing a much better image. You should observe the animals you intend to photograph for multiple dives if possible, and learn their behavior. The cuttlefish in the top right are two males who were following a larger female around in hopes of mating with her, and the bottom left image is of a cuttlefish feeding with it’s long tongue out catching it’s prey. Once you know what the behavior of an animal is, you can watch for it and be more prepared to capture it. Another tip is to get down at the animals level, in this case, right on the sand and shoot a face-on image.

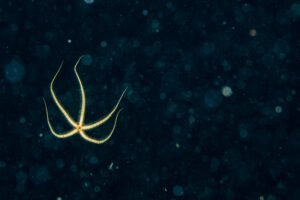

What could be more fantastic than a larval wonderpus? These animals are a rare find and can be very difficult to photograph but there are some things that you can do to ease the pain. A larval wonderpus is usually found during a blackwater dive near muck sites such as Lembeh or Anilao. During the night, they rise up from deep in the ocean to shallower depths to feed, so they are found at night over deep water.

Shooting larval animals at night has many challenges, the least of which is finding the critter in your viewfinder. You can help your cause by taking two lights down with you; a focus light attached to your camera rig for focusing, and a torch (with a lanyard around your wrist so you can drop it without losing it) to help you search for critters. In addition, use a lens that has a shorter focal length such as a 60mm. Yes, you will have to crop, but your working distance is smaller with a shorter lens, and in the dark it is already difficult enough to focus on tiny, clear plankton without adding distance into the mix. Use two strobes, pointed toward each other and slightly out front of your housing to minimize backscatter. You should also consider using a higher ISO (500 or so) while keeping your other settings around f/16 (or higher) and 1/200th. Last, but not least, don’t become too frustrated and remember to have fun. This is a challenging subject and dive to tackle, but the results can be spectacular!

Cryptic animals can be some of the most difficult animals to photograph. They usually blend in with their environment so well, that they are hard to find in the first place, let alone photograph. I have found that a snoot is the best tool for these types of animals. With a snoot, you can light just the animal, and not any of its surrounding habitat. The nudibranch above is a Melibe colemani and looks like a ball of string if it isn’t isolated from its environment. A snoot will help block light from reaching the habitat surrounding it. Another good example of this is the Ornate ghost pipefish which has outstanding camouflage. Adding a snoot to light up just the fish makes all the difference.

Ornate Ghost Pipefish

Some animals have so much decoration on their bodies that they appear to be a part of the reef. The tasseled wobbegong is a great example of this type of camouflage. They are difficult to isolate from their background because they are much too large for a snoot. In this case, the animal’s position may be as much of a factor as lighting is.

The animal above was resting in a way that there was a little space between his tassels and the reef. By bringing the strobes up overhead, the light is cast down, using the animal’s own shadow to bring out its shape, and isolate it from the reef below.

The wobbegong in the image below is resting closer to the sand, with no space for a shadow. In this case, it is much harder to make an image where it appears separate from its environment. If your viewers cannot tell that there is an animal in the picture, then it probably isn’t worth showing in public.

Other fantastic beasts have “hair” or fibers that look like hair, that make them very difficult to photograph. Take a look at the group of images below.

Rhinopias

Ambon Scorpion Fish

Hairy Frogfish

Each of these animals has multiple appendages that help camouflage it. But when they are photographed with front facing light, they disappear into the background, or look dull.

Photographing them with light from behind brings out the animal without lighting the background. You can use a hand held torch placed behind the animal, or a remote strobe or video light to backlight all the “hair” so that the animal stands out.

Rhinopias

Ambon Scorpion Fish

Hairy Frogfish

There are many fantastic beasties in the oceans and some are very rare. In our excitement to prove that we saw one of these special animals, sometimes we don’t take the time to photograph them well, preferring to have an ID photo rather than go home empty handed. With these tips for how to shoot them, you can be better equipped to take outstanding images of your fantastic finds.

Join me for a workshop! Travel to a great destination where you will have exclusive coaching on your underwater photography. Meet new people, network, try new techniques, and learn with the pros! Click on Travel and Workshops for more information!

Subscribe now!

As always, if you enjoy my images please visit my website, waterdogphotography.com, or give me a like on Facebook at Waterdog Photography Brook Peterson. Don’t forget to follow me here at waterdogphotographyblog and please feel free to share on Facebook or other social media.

My photographs are taken with a Nikon D810 in Sea and Sea Housing using two YS-D2 Strobes.

All images and content are copyrighted by Brook Peterson and may only be used with written permission. Please do not copy or print them. To discuss terms for using these images, please contact me.

copyright Brook Peterson 2019